In a farmhouse in Cordoba between brambles and oleanders lived a saddler-man with a saddler-woman ...

Federico García Lorca in New York and the Other Spaniards

On García Lorca's Poet in New York

García Lorca in New York

Garcia Lorca's passport.

A picture relevant to García Lorca's works

The cancelled presentation

An acquaintance visits the García Lorca's exhibit at the NYPL on 42nd St at Fifth Avenue.

The recounting of the Missing Poet.

García Lorca at Columbia University.

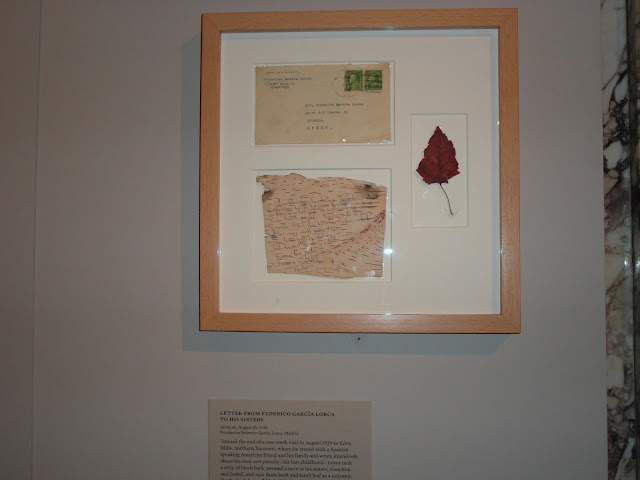

A display of documents at the New York Public Library

La guitarra de la que el poeta habla en sus poemas

La Argentina

García Lorca's business correspondence.

Other Documents Originales y Correspondencia.

The Poet who would not return.

A Poet in New York

During my junior year in high-school, I got the chance to

interpret the character of shoemaker in the La Zapatera Prodigiosa (The

Shoemaker's Prodigious Wife) play by Federico García Lorca. It was a fun experience which I shared with

beautiful red-headed Rosalía Donofrio, who played the female saddler After the high-school experience at Humboldt in

the Normal School Theater, I eventually saw her as a psychology student at

Universidad del Norte for a few years, and it is possible that we might have

graduated on the same ceremony a few years later. However, this was my only

major dramatic experience, as an actor with deep penetration in the psychological

understanding of the character, and the social and personal content of the

drama.

Just a few weeks ago, I walked into the lower level room at the

New York Public Library on 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue with an

acquaintance to see the exhibit on Back Tomorrow, displaying a few important

documents and late writings by Garcia Lorca, who happen to become my favorite

Spaniard poet after my unique dramatic experience. The New York exhibit

presented the scenario and documents prior to his death, and a collection of his literary works. García Lorca never return after his famous “back tomorrow”, as

he was killed in Spain during the civil war. And his book Poet in New York was published

During my school and college years, there were several attempts

for an insight in the Spanish literature and my only major interaction came

along when I got a copy of La Vida es Sueño by [Don] Pedro Calderón de la

Barca, which came to me accidentally, as it had been given as a reading

assignment to my brother César at Colegio de San Francisco de Asís, and I

stumbled onto the book and carefully read it.

As if dreams freed the soul, the topic of dreaming to live, or living

the dream or trying to dream to attain what we might have physically or materially in the immediate future, became an important leit motif in

some of my short stories, and has significantly influence the creative nature

of my poetry from the hispanic perspective, beyond the most significant

admiration and drills on Musset, Victor Hugo, Baudelaire, and some other of my

favorite French poets.

However, the greatest and best known Spanish poet is probably

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer. He was indeed the most studied and analyzed through my

formal school coursework. In particular, Rimas y Leyendas (Rhymes and Legends),

represented the most significant work by a Spanish poet of his time.

Bécquer’s rhyme LIII

(Rima LIII)

Volverán las oscuras

golondrinas

En tu balcón sus nidos a

colgar

Y otra vez con el ala a sus

cristales,

Jugando llamarán.

Pero aquellas que el vuelo

refrenaban

Tu hermosura y mi dicha a

contemplar,

Aquellas que aprendieron

nuestros nombres,

¡Esas... no volverán!

In English:

The dark swallows will

return

their nests upon your

balcony, to hang.

And again with their wings

upon its windows,

Playing, they will call.

But those who used to slow

their flight

your beauty and my

happiness to watch,

Those, that learned our

names,

Those... will not come

back!

Rhyme XXI (Rima XXI)

¿Qué es poesía?, dices

mientras clavas

en mi pupila tu pupila

azul.

¡Qué es poesía! ¿Y tú me lo

preguntas?

Poesía... eres tú.

A harsh translation into English reads:

What is poetry? you ask,

while fixing

your blue pupil onto mine.

What is poetry! And you are

asking me?

Poetry... is yourself.

And through my life, I have indeed read many antologies on the

Spanish literature. Beyond my admiration

of Don Quijote and my studies both in Spanish Literature and through French

Literature studies on Le Quixote in comparison to La Chanson de Rolland and

other Gallic and French Troubadour writings, and further beyond my literary

analysis of the Spanish historic and Spanish historic-religious genres in the

novel category, there have been many poets that have certainly impressed me.

The list is simply too long, but I could highlight some such as:

Rafael Alberti (1902–1999), Vicente Aleixandre (1898–1984) -

Nobel Laureate 1977, Dámaso Alonso (1898–1990),

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer (1836–1870), Baltasar del Alcázar (1530–1606),

Jorge Guillén (1893–1984), Juan Ramón Jiménez (1881–1958) - Nobel Laureate

1956, Antonio Machado (1875–1936), Pedro Salinas (1892–1951),Garcilaso de la

Vega (1503–1536),José de Espronceda (1808–1842). They have mostly influenced South American poets, such as Jorge Luis Borges, César Vallejo, and Guillermo Valencia, among others.

But finally retaking García Lorca, it was an exciting experience to visit his exhibit an enjoy with friends and acquaintances of various nationalities a celebration of our Hispanic culture.

But finally retaking García Lorca, it was an exciting experience to visit his exhibit an enjoy with friends and acquaintances of various nationalities a celebration of our Hispanic culture.

Poems by García Lorca

A tree of blood soaks the morning

where the newborn woman groans.

Her voice leaves glass in the wound

and on the panes, a diagram of bone.

The coming light establishes and wins

white limits of a fable that forgets

the tumult of veins in flight

toward the dim cool of the apple.

Adam dreams in the fever of the clay

of a child who comes galloping

through the double pulse of his cheek.

But a dark other Adam is dreaming

a neuter moon of seedless stone

where the child of light will burn.

Adivinanza De La Guitarra

En la redonda

encrucijada,

seis doncellas

bailan.

Tres de carne

y tres de plata.

Los sueños de ayer las buscan

pero las tiene abrazadas

un Polifemo de oro.

¡La guitarra!

Cantos Nuevos

Dice la tarde: '¡Tengo sed de sombra!'

Dice la luna: '¡Yo, sed de luceros!'

La fuente cristalina pide labios

y suspira el viento.

Yo tengo sed de aromas y de risas,

sed de cantares nuevos

sin lunas y sin lirios,

y sin amores muertos.

Un cantar de mañana que estremezca

a los remansos quietos

del porvenir. Y llene de esperanza

sus ondas y sus cienos.

Un cantar luminoso y reposado

pleno de pensamiento,

virginal de tristeza y de angustias

y virginal de ensueños.

Cantar sin carne lírica que llene

de risas el silencio

(una bandada de palomas ciegas

lanzadas al misterio).

Cantar que vaya al alma de las cosas

y al alma de los vientos

y que descanse al fin en la alegría

del corazón eterno.

Garcia Lorca’s Main Works

Poetry collections

• Impresiones y paisajes (Impressions and

Landscapes 1918)

• Libro de poemas (Book of Poems 1921)

• Poema del cante jondo (Poem of Deep Song;

written in 1921 but not published until 1931)

• Suites (written between 1920 and 1923,

published posthumously in 1983)

• Canciones (Songs written between 1921 and

1924, published in 1927)

• Romancero gitano (Gypsy Ballads 1928)

• Odes (written 1928)

• Poeta en Nueva York (written 1930 – published

posthumously in 1940, first translation into English as The Poet in New York

1940)[57]

• Seis poemas gallegos (Six Galician poems

1935)

• Sonetos del amor oscuro (Sonnets of Dark Love

1936, not published until 1983)

• Lament for the Death of a Bullfighter and

Other Poems (1937)

• Primeras canciones (First Songs 1936)

Play

• Christ: A Religious Tragedy (unfinished 1917)

• El maleficio de la mariposa (The Butterfly's

Evil Spell: written 1919–20, first production 1920)

• Los títeres de Cachiporra (The Billy-Club

Puppets: written 1922-5, first production 1937)

• Mariana Pineda (written 1923–25, first

production 1927)

• La zapatera prodigiosa (The Shoemaker's

Prodigious Wife: written 1926–30, first production 1930, revised 1933)

• El público (The Public: written 1929–30,

first production 1972)

• Así que pasen cinco años (When Five Years

Pass: written 1931, first production 1945)

• Bodas de sangre (Blood Wedding: written 1932,

first production 1933)

• Comedia sin título (Play Without a Title:

written 1936, first production 1986)

• La casa de Bernarda Alba (The House of

Bernarda Alba: written 1936, first production 1945)

Los

sueños de mi prima Aurelia (Dreams of my Cousin Aurelia: unfinished 1938)